Introduction

Chronic wounds are a major public health issue resulting in a significant financial burden on the healthcare system [1,2]. Furthermore, these wounds can result in serious systemic infections, frequent hospitalizations, surgical procedures, and amputations of extremities which leads to severe emotional and physical stress for patients. The burden of chronic wounds is anticipated to rise even more significantly with an aging population, increasing chronic diseases such as diabetes and obesity, and a lack of investment in research funds to develop new treatment strategies. Collaborative ef-forts must be made towards understanding the various pathologies underlying this extensive health problem in order to develop novel therapeutic strategies.

In chronic wounds, a constant state of inflammation due to complex interactions between microbes and the wound microenvironment exists [3]. Wounds that fail to heal express high levels of various pro-inflammatory cytokines, decreased levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, and exhibit markers of an enhanced host immune response. Biofilms, which are defined as communities of bacteria that have grown on surfaces of tissues or medical devices protected by an ex-trapolysaccharide matrix, are becoming increasingly recognized as a major obstacle in proper healing [4]. Biofilms are often present in chronic nonhealing wounds and inhibit the ability of the immune system to eradicate the bacteria, causing a constant pro-inflammatory response [5]. Therefore, a com-prehensive approach to treat chronic wounds must be able to target biofilms. If a biofilm is suspected clinically, the only cur-rent definitive treatment is surgical debridement, which can be an invasive and ineffective treatment option. Therefore, novel treatment options are needed. One potential solution to this problem involves the use of stem cells, which could help to restore normal physiologic conditions and remove bacteria in the wound through the secretion of paracrine factors. Paracrine factors are defined as trophic factors released by stem cells in response to the microenvironment [6,7]. The multi-potency of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) coupled with their immunomodulatory properties through specific paracrine interactions with the immune system in damaged tissues have made these cells an attractive option to accelerate the healing process in chronic wounds [8]. Accordingly, the objective of this study was to examine the effects of paracrine factors secreted from MSCs on reducing infection and accelerating wound closure in biofilm-infected wounds. We hypothesized that paracrine factors from MSCs could improve wound healing in biofilm-infected wounds.

Methods

Mesenchymal stem cells

Human MSCs were isolated from the iliac crest bone marrow of healthy donors after obtaining written informed consent. Institutional review board approval of the protocol was grant-ed by Tulane University. MSCs were harvested from donors using previously described techniques [9]. Human MSCs were used between 2–6 passage numbers and were grown in alpha-minimum essential media (MEM) supplemented with 10% fe-tal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 µg/mL of strep-tomycin, and 100 U/mL of L-glutamine under standard tissue culture conditions. Prior to each experiment, MSCs were pas-saged, centrifuged, and resuspended to 107 cells/mL in alpha-MEM.

Seeding of MSCs onto extracellular matrix

MSCs were seeded onto porcine small intestinal submucosa (SIS; Surgisis Biodesign, Cook Surgical, West Lafayette, IN, USA) as previously described [10]. The SIS was cut into 5 mm discs and rehydrated in sterile phosphate-buffered saline for 15 minutes prior to use. Fifty microliters of cells (1.0×107) were added to each SIS disc of extracellular matrix (ECM) in the plate. Cells were incubated on the ECM for 30 minutes be-fore the remainder of the well was filled with media. After 24 hours, ECM seeded meshes were moved to new wells to prevent the collection of paracrine factors from any MSCs growing on the bottom of the wells and not on the mesh.

Collection of MSC paracrine factors

Cell culture media was completely exchanged 24 hours prior to collection of paracrine factors for the static/ECM seeded MSCs. The collected media was fractionated using 3 kDa Am-icon Ultra-4 centrifugal filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) at 3,200 × g and stored at –20°C. Paracrine factors were collected at days 1, 3, and 7.

Analysis of paracrine factors from MSC supernatant

All samples were analyzed using the Milliplex Multi Analyte Profiling Human Cytokine/Chemokine 14 analyte premixed kit (Millipore) following the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were assayed in duplicate wells (25 μL per well) and the mean was determined. The plates were read with a Bioplex analyzer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Cytokine concentrations were calculated in pg/mL based upon an eight-point five-parameter logistic standard curve for each cytokine. The values were normalized at each time to the number of viable cells. The cytokines studied included: granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon (IFN)-gam-ma, interleukin (IL)-1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha.

Bacterial growth

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (strain PAO1) bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium overnight. Cultures were diluted to 105 colony forming units (CFU) and 2 µL of each diluent was inoculated onto the surface of sterile filter paper (5 mm diameter, 0.2 µm pore size; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) embedded in an agar plate [11]. Biofilms were grown for 72 hours at 37°C and moved to a fresh agar plate at 24 and 48 hours. The 105 CFU were quantitated per membrane.

Animals

Adult BALB/cJ male mice (8–12 weeks old) obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were used for all experiments (n=17). All animals were housed in individual cages under constant temperature and humidity with a 12-hour light/dark cycle with access to chow and water ad libitum throughout the study. All animal procedures and care were reviewed and approved by the Tulane University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC No. #4261) and performed in accordance with all Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International and IACUC standards.

Excisional wound protocol

Mice were individually anesthetized with isoflurane. Hair was removed from the dorsal surface with a depilatory agent and rinsed with an alcohol wipe. The site was prepped with beta-dine and draped. Sterile technique was maintained throughout the entire procedure. A 5mm punch biopsy was used to outline a pattern for the wound on one side of the mouse's dorsum. One wound was created per mouse. Full thickness wounds were created using Iris scissors to extend through the panniculus carnosus. A 10-mm square-shaped splint fash-ioned from a 0.5mm thick silicone sheet (Grace Bio-Labora-tories, Bend, OR, USA) was positioned with the wound cen-tered within the splint. An immediate-bonding adhesive (Kra-zy Glue; Elmer's Inc., Columbus, OH, USA) fixed the splint to the skin, followed by interrupted 4-0 PDS sutures to stabilize its position. A 10-mm square antimicrobial dressing (Telfa; Covidien, Mansfield, MA, USA) with a 5mm hole in the cen-ter to prevent contamination of the wound with any surrounding skin bacteria was placed over the silicone splint and the wound was dressed with a sterile semi-occlusive transparent film dressing (Tegaderm; 3M Health Care, St. Paul, MN, USA). This dressing did not contain any antimicrobial agents. The mice were wrapped around their midline with a self-ad-herent wrap (Coban; 3M Health Care) to protect the wound. All mice received the same type of dressing.

Post-surgical care of animals

All mice received 0.9% NaCl (50 cc/kg) and buprenorphine (0.01–0.03 mg/kg) subcutaneously each day following surgery. They were also given a liquid diet (DietGel; ClearH2 O, Portland, ME, USA) to avoid dehydration post-surgery. Mice were weighed every 2 days during dressing changes and were euthanized if they lost greater than 30% of their original body weight.

Biofilm inoculation

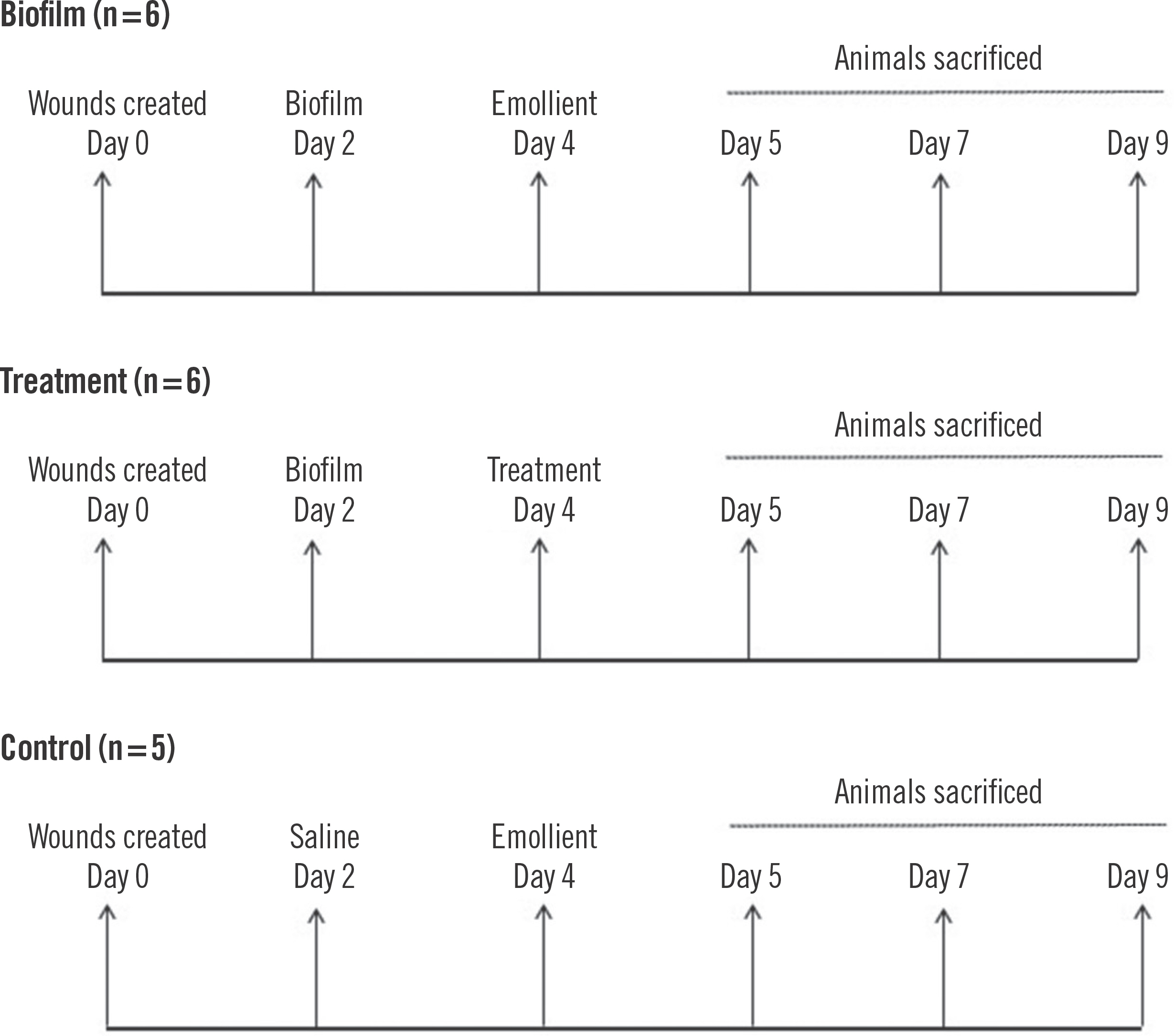

On post-surgery day 2, mice in the biofilm group (n=6) and the treatment group (n=6) were inoculated with 105 CFU P. aeruginosa biofilms by inverting the filter paper and sliding the biofilm onto each individual wound. For the control arm, the wounds received sterile saline (n=5). Wounds were re-dressed with antimicrobial pads and a sterile occlusive Tega-derm dressing every 2 days. The wounding strategy for this study is outlined in Fig. 1.

Wound morphology

Digital photographs of each wound were taken every 2 days. A camera was affixed onto a stand to allow for a standard distance to the mice. The area of each wound was measured in pixels using image analysis software (Image J, v1.44; NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Post-wounding measurements were normalized to the corresponding day 0 wound area and re-corded as a percentage of the original wound area. Validation of area measurements was performed as previously described [12]. Briefly, a stencil was used to draw a perfect circle with an area equal to 1.99 mm2 and the number of pixels was determined. Ten identical measurements were performed on wounds to obtain an average to use for other wounds. For each mouse, the wound size was compared to itself to express percentage change from the original wound size throughout the study period.

Treatment

Concentrated media (100 µL) from MSCs grown on SIS for 7 days was mixed with an equal amount of petroleum ointment (Aquaphor; Beiersdorf Inc., Wilton, CT, USA) and applied topically to each wound in the treatment group at post-surgery day 4. The same ointment without MSCs was applied to wounds of the other (control and biofilm) groups on the same day.

Bacteriology of the wounds

At post-surgery days 5, 7, and 9, mice were sacrificed from all three groups. A 5mm punch biopsy was used to excise the wound. All tissues were weighed and homogenized in sterile saline. The homogenate was serially diluted and plated on LB agar and incubated at 37°C overnight to quantitate CFU. Car-diac puncture was also performed at the time of sacrifice to obtain blood cultures and 0.1 mL was plated on LB agar and incubated at 37°C overnight.

Histological analysis

Wounds were harvested using a 10-mm punch biopsy and bi-sected at their largest diameter for staining. They were pre-served in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). A pathologist blinded to the samples evaluated the epithelial gap size in each sample with light microscopy at a magnification of 200×.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess for normal distribution of the data (SPSS version 27; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Significance of the treatment group compared to the biofilm group was determined using an unpaired two-tailed Student t-test. A P-value ≤0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Supplementary Table 1 outlines the weight of the mice and the experimental strategy.

Results

MSC supernatant and cytokine analysis

Detectable levels of all 14 cytokines were found in the supernatant from MSCs grown on the ECM. Higher levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines GM-CSF, IL-6, IL-8, and MCP-1 were detected after 7 days of growth. There was no change in levels of IFN-gamma, IL-1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-10, IL-12, IL-13, and TNF-alpha detected at 7 days.

Mice physical health

In pilot studies, it was determined that inoculums of biofilm >105 CFU led to a significant weight loss and mortality (data not shown). Therefore, the inoculum of 105 CFU was chosen. No mice were found to have >102 CFU in the blood cultures at the time of sacrifice. At day 0, the BALB/cJ mice ranged in weight from 20.7–31.6 g. Average weight in the control group was 26.1±1.7, average weight of the biofilm group was 28.2± 0.5, and average weight of the treatment group was 26.2±0.6. No statistical significance was found (P>0.05).

Histology

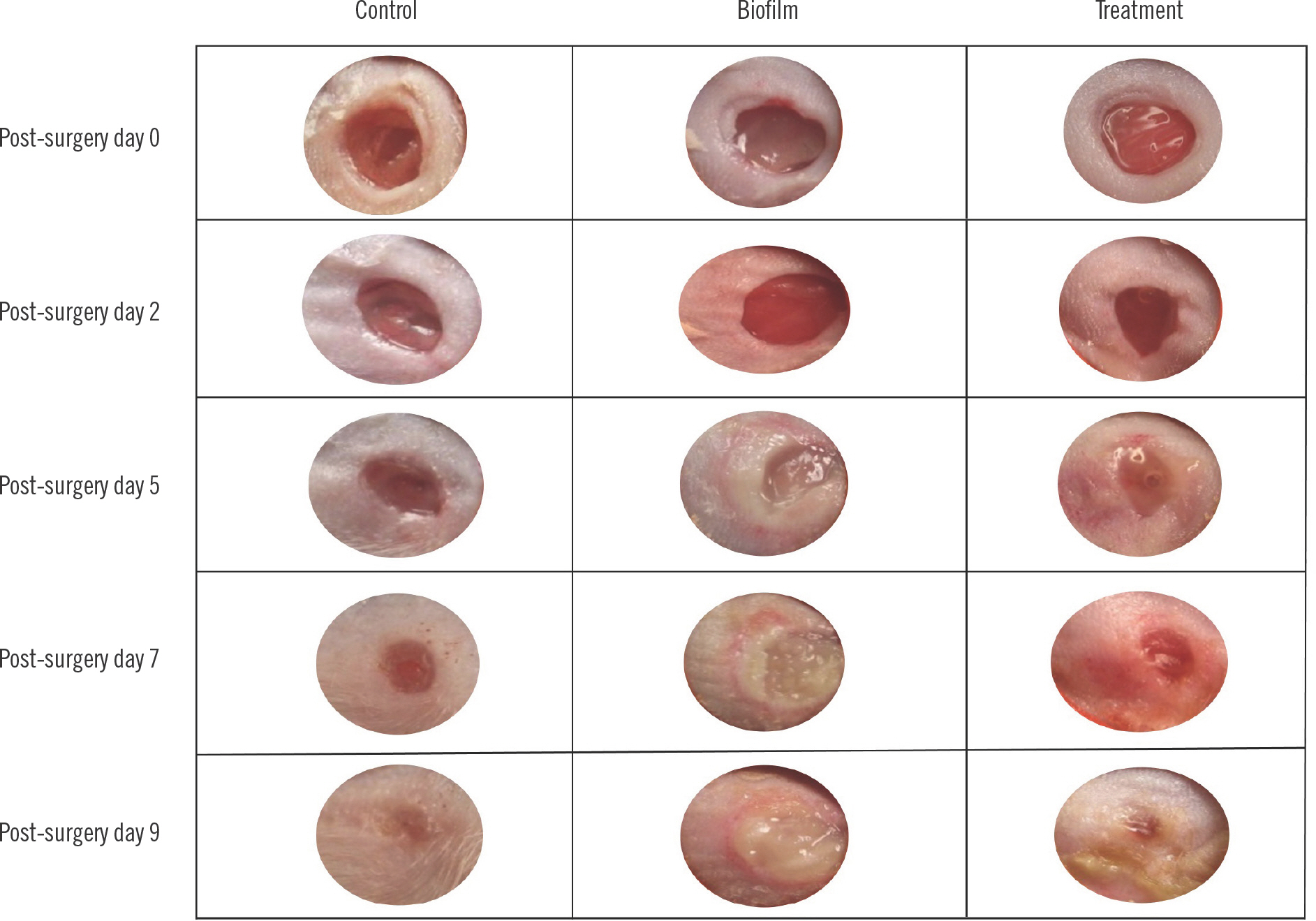

To confirm the presence of delayed healing in infected wounds, H&E staining was performed to evaluate the samples for wound closure (Fig. 2). In the control group, a loss of the epidermal layer and the presence of a 2 mm ulcer was found at post-surgery day 5. The samples at post-surgery days 7 and 9 did not have ulcers. H&E analysis of the biofilm-infected wounds revealed a loss of epidermal layer and ulcer formation in all samples with the ulcer size ranging from 4–5 mm.

Wound closure

Morphological changes in the wounds for all three groups during the course of the experiment are shown in Fig. 3. The control group wounds were consistent in morphology and did not display significant bleeding. The wounds almost completely closed by post-surgery day 9. Ulcers with thick purulent ex-udate formed on the biofilm group and were still apparent by post-surgery day 9 (post-infection day 7). The treatment group also demonstrated ulcer formation with resolution on post-surgery days 7 and 9 (post-infection days 5 and 7).

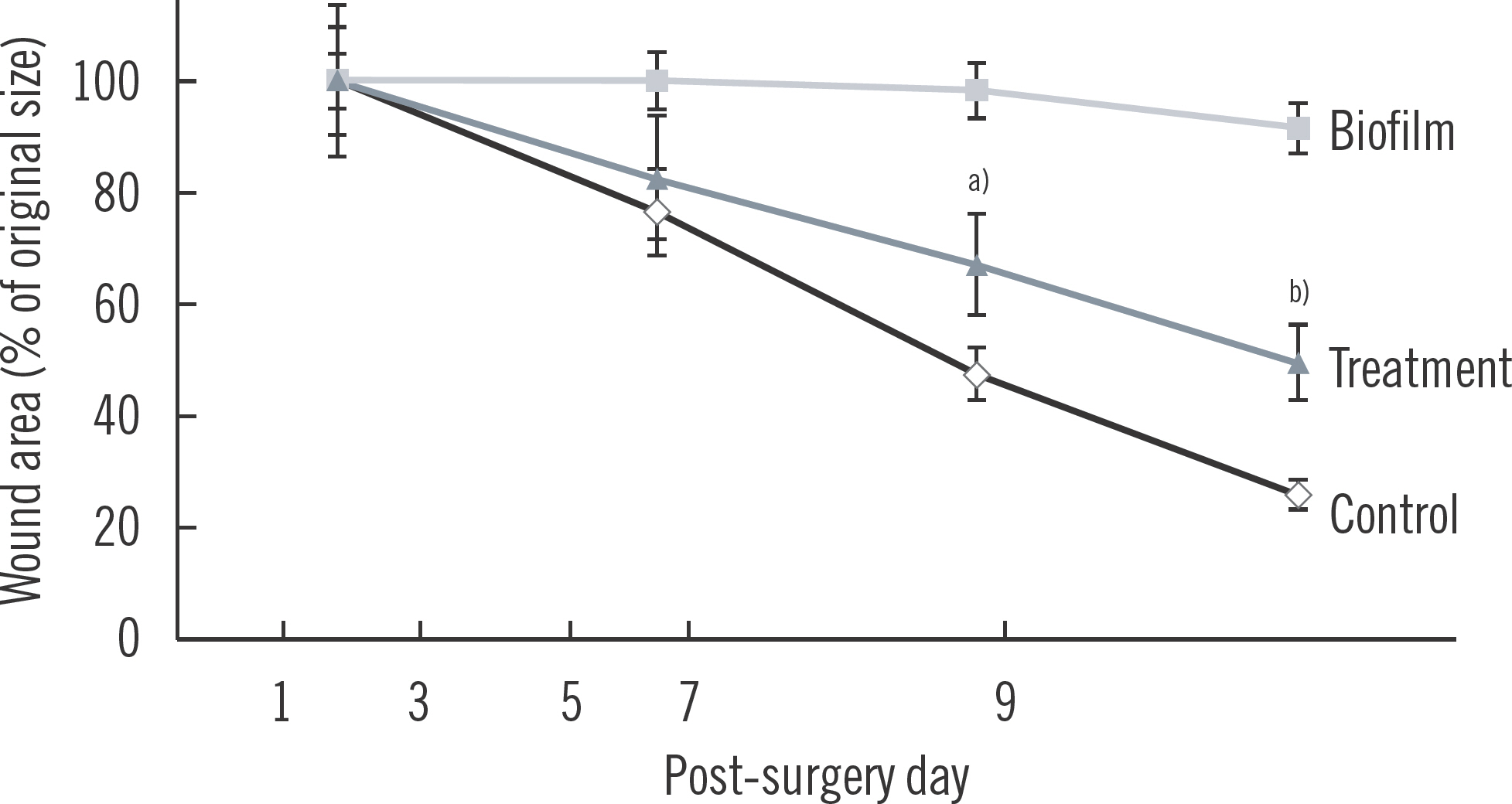

The control group had an average of 26.1%±6.5% of the original wound area by post-surgery day 9. In contrast, the biofilm group had an average of 81.4%± 0.3% of the original wound remaining on post-surgery day 9 (post-infection day 7). The treatment group had 39.8%±10.2% of the original wound area remaining at post-surgery day 9 (post-infection day 7 and post-treatment day 5).

The biofilm control, which represented wounds infected with biofilm and treated only with ointment not containing any paracrine factors had 91.4% of the original wound area remaining at post-surgery day 9. All data were determined to be nor-mally distributed (Supplementary Table 2). A statistically significant difference in the percentage of original wound remaining was found for the biofilm group versus the control group at post-surgery days 7 and 9 (P=0.03 and P<0.001). The wound areas remaining are shown in Fig. 4 and Table 1.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of wound remaining in mice groups (control, biofilm, and treatment). a) P=0.03 vs. biofilm day 7; b) P<0.001 vs. biofilm day 9.

Table 1.

Average percentage of wound remaining open for control group, biofilm group, and biofilm group treated with paracrine factors from mesenchymal stem cells

| % Open wound | Control (n=5) | Biofilm (n=6) | Treatment (n=6) | P-value | Degree of freedom | T statistic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-surgery day 5 | 76.6 (7.5) | 100 (0) | 83.6 (8.6) | 0.09 | 10 | 1.907 |

| Post-surgery day 7 | 47.7 (5.8) | 98.2 (0.8) | 67.4 (11.8) | 0.03 a) | 10 | 2.604 |

| Post-surgery day 9 | 26.1 (6.5) | 91.4 (0.3) | 39.8 (10.2) | <0.001 a) | 10 | 5.057 |

Bacteriology

The numbers of viable bacteria in wounds were quantified by plating tissue homogenates (Table 2). Control wounds had less than 102 CFU/g tissue at each time point of sacrifice. The biofilm group had a consistent number of bacteria at post-surgery days 5, 7, and 9 with 1.9×106 CFU/g tissue, 8.0×106 CFU/g tissue, and 8.9×106 CFU/g tissue, respectively. The biofilm vehi-cle mouse had 6.4×106 CFU/g tissue of bacteria, which is consistent with the biofilm group. The treatment group had a simi-lar number of bacteria at post-surgery day 5 (6.2×106 CFU/g tissue) but had decreased numbers at post-surgery day 7 (8.4×105 CFU/g tissue) and day 9 (6.8×105 CFU/g tissue). PAO1 bacteria were differentiated from skin flora by colony size and morphology.

Table 2.

Quantitative bacteriology for wound biopsies at 5, 7, and 9 days after surgery

Discussion

Chronic wounds are a significant source of morbidity and mortality in the healthcare field. This study used a well-established in vivo biofilm model [13,14] to evaluate the treatment of biofilm-infected wounds with paracrine factors from MSCs. The results from this study suggest that the conditioned media from MSCs grown on an ECM for 7 days containing pro-inflamma-tory paracrine factors accelerated the rate of wound closure and decreased the bacterial burden in an animal model.

Previous studies have demonstrated that stem cells have an effect on the wound healing process [8,15,16]. The paracrine factors from MSCs have also been studied for their role in wound healing [17]. Chen et al. [18] identified vascular endothelial growth factor-alpha, IGF-1, EGF, keratinocyte growth factor, angiopoietin-1, stromal derived factor-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 alpha and beta and erythropoietin secretion from MSCs compared to dermal fibroblasts. MSCs have been shown to secrete antimicrobial peptides, such as LL-37 and lipocalin-2 which may be important factors in the erad-ication of biofilms [19]. These peptides have already been used to treat biofilms in vitro with varying success [20]. A recent study by Yang and colleagues demonstrated that co-culture of P. aeruginosa biofilms with MSCs derived from human umbilical cords prevented the development of biofilms on an endo-tracheal tube presumably due to production of LL-37 [21]. Further studies are needed to determine what specific Paracrine factors of the conditioned media have measurable anti-biofilm properties that can influence wound healing in vivo, and to identify additional paracrine factors which may be critical to the interactions of biofilm formation and wound healing.

There are few well-studied biofilm models and even fewer have been used to evaluate the different treatment strategies of biofilms [22]. A study by Seth et al. [22] investigated surgical debridement, lavage, and silver sulfadiazine in the treatment of biofilms using a rabbit ear model. They determined that the combination of all three treatment strategies improved wound healing significantly. A previous study by Hayward et al. [23] found that when fibroblast growth factor was applied to chronic granulating wounds in rats, a significant acceleration in wound healing was observed but no change in the bacterial counts was found.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the number of mice for the treatment group was too low to reach statistical significance. In addition, mouse skin heals primarily by contraction in comparison to human skin which heals largely by epithelization. The healing process of the animal model was altered through using a silicon ring to prevent contraction, however, there are still some limitations with translating these results to human skin [24]. Second, the time course could be increased to further evaluate the remodeling phase of wound healing. Mice were evaluated for 9 days in this experiment during the inflammatory and proliferative phases of wound healing. A longer time period wound be necessary to assess the chronic healing process [13,14]. Finally, it is important to evaluate the effect of unprogrammed (i.e., static seeded) MSCs on the wounds to determine how cells grown in standard tissue culture conditions affect the bacterial counts. Previous studies have already demonstrated that these MSCs accelerate the rate of closure in aseptic wounds [18,25].

In conclusion, the results from this study demonstrated a novel treatment strategy for chronic wounds using the Paracrine factors secreted from reprogrammed MSCs to decrease bacteria counts and accelerate wound closure in an animal study. Wound healing is a dynamic process that involves many different types of cells. Existing strategies to heal chronic wounds that focus on one or two agents are too simplistic. MSC-based paracrine factor therapies offer the advantage of several cytokines, growth factors, and peptides being secreted at different stages, which may be critical for the development of novel strategies to heal wounds.